|

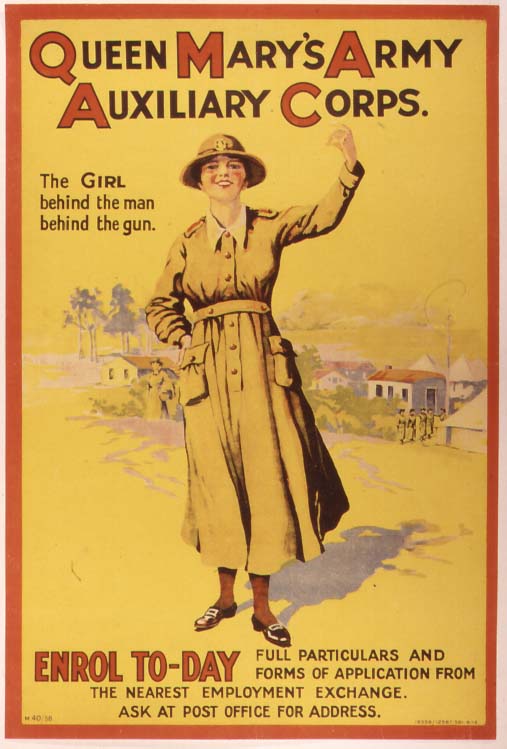

Here's a flavour of our WWI show. The Great War is an immense, overwhelming subject and we don't try to cover it all in just 90 minutes. Instead, we concentrate on human reactions to the War, as expressed in writings of the time and our own reconstructions of events and conversations. |

Joining Up

|

Robert Vernede |

I never said anything about enlisting when I went home that night, and on the Sunday morning there was an OHMS envelope. I didn't open it. So when breakfast started Mother said, "What's that? Get it opened." I didn't want to open it but she insisted. The instructions were to report to the Drill Hall, Grange Road. When I read that out, "Jack," she says to Dad, "stop his gallop. He doesn't go! There's lots that will go before that boy goes." So Dad says, "Have you joined, Pete?" I said, "Yes, Dad." "Well," he said, "this is a nice how-do-you-do."

Then Mother started to get excited. She said, "Stop his gallop, Dad. He's not going." So Dad said, "Just supposing, Pete, you came back with a leg or arm off? Who wants you?" I said, "Let me get there first, Dad, Before I get back." "So," he said, "it's all right you talking like that, but you don't know what you've done." I said, "But I do know what I've done." "All right," he said, "if you've made your bed, you'll have to lie in it." I said, "I'll lie in it, Dad." "Well, he said to Mother, "there's no more to be said, Polly." And that was the start.

| In December 1915 this notice appeared in the Church Lads Brigade

Gazette:

"We hear from the Front that in addition to socks, mufflers and mittens (with thumb only) will be greatly appreciated. We hope that committees of ladies will be formed in different Companies and districts and forward quickly to the Headquarters' Chaplain both mittens and mufflers. The Battalion wants 1,200 of each before the end of the month. If kind friends cannot get to work, will they please send him a donation to buy mufflers and mittens." |

|

A strange perversion of the English language - a peculiar form of faux-heroic mediaevalism - became prevalent in the newspapers and magazines of the time. Here we imagine a newspaper editor briefing his staff on the correct form to use when reporting the War:

EDITOR: Let me make it quite clear from the start that this newspaper has a vital part to play in winning the war. It's our duty to make sure that everyone in the country reads the right news, written in the proper style. Anything else will sabotage civilian morale and sap the will of the nation.

SUB: What do you mean, sir, "the right news"?

EDITOR: Oh you, Jenkins. The right news, for those of you who are too young to remember, is the news that the War Office passes on to us. Anything else is just speculation - and the Courier does not print speculation, does it? No, it does not. But just as important as printing the right news is phrasing it properly and using the right words.

So, for example, a British infantryman is not just a soldier; he is a warrior. He faces peril with pluck. Naught will suffice but that he ardently perform stern deeds to vanquish the foe. He is staunch and valorous and manly and gallant and comradely. If he dies, or perishes, in the course of assailing the host, we say that he has joined the fallen.

You will find a complete list of approved expressions on your desks when you return. Thank you, and good morning, gentlemen.

The Western Front

|

|

Troops didn't spend all their time in France and Belgium performing night sorties from front-line trenches, whatever some films and television series might like you to believe. Rather, they were rotated around the front line and reserve trenches and spent some time regrouping and resting behind the lines. The time would inevitably come, though, when you would find yourself in the front line, facing the combination of alternating tedium and terror that was trench warfare.

We presented a reconstruction of a typical day in the life, or death, of a unit on the front line of the Western Front.

A CORPORAL, SERGEANT, PRIVATE, CAPTAIN, SUBALTERN and another PRIVATE step up in turn and face the audience:

CORPORAL: Well, the day starts about an hour before first light - that would be at about half past four - with stand-to. You see, dawn's a popular time to launch an attack, so what we have to do at stand-to is this: everyone gets up on to the fire-step, weapon at the ready, and gazes out towards the German line. When it's almost light, and it's obvious that Fritz isn't up to anything, we stand down, and get on with breakfast.

SERGEANT: This is rations of bread, bacon, and dixies full of tea which've been brought up during the night. We fry the bacon in mess-tin lids. A welcome extra - this depends on your general in command - is rum. We get about two tablespoons each. I drink it straight, but some of the lads like to put it in their tea. To my mind, though, this ruins a decent cup of tea and a decent tot of rum.

1ST PRIVATE: Before an attack, they give us extra rum. It's supposed to take your mind off what's going to happen, and also, if you do cop one, it might just take the edge off the pain a bit.

SERGEANT: Me, I'm scared sober throughout.

1ST PRIVATE: The daytime is taken up in cleaning weapons, repairing damaged sections of trench, trying to get rid of the confounded body lice, which are bloody everywhere, or we write letters or sleep.

CAPTAIN: As Company Commander, my duties are rather different. I have the men's letters to censor, and there are vast amounts of paperwork, most of it, between ourselves, pointless. A report of the previous night's events, well, that's one thing, and very necessary, but the runner's always bringing me damn-fool messages, like "Have your men had porridge this morning?" You're trying your hardest to get intelligence back to Headquarters about something really vital - an attack, say - and you get this message, "Please send number of picks and shovels on your sector." And they expect you to give this priority!

SUBALTERN: We junior officers are different again. We have to perform inspections, encourage the men, and walk around looking as though we couldn't care less about our possibly imminent death - like The Man Who Broke The Bank At Monte Carlo, I often think.

CORPORAL: It works, though! You see him casually strolling around, just as if he was walking down Piccadilly - you'd never guess Fritz was a few hundred yards away. Nerves of steel, that one's got.

CAPTAIN: It also falls to me to write letters of condolence. I always try to say something good, and I usually mean it. But if a man hasn't died well, or if I don't even know how he's died, the relatives still need to hear something comforting.

2ND PRIVATE: Then there's sentry duty, working parties - parties! - that always makes me smile. But of course, what you mustn't do is let yourself be seen above the parapet. The snipers'll take the top of your head off, just like that.

SERGEANT: We start work again after evening stand-to. Repairing the wire, digging saps, carrying up rations and mail.

2ND PRIVATE Also carrying materials for trench repairs - timbers, duck-boards, sandbags, tarpaulins, pumping equipment.

1ST PRIVATE: It rains and rains and rains! All the bloody time, it seems.

2ND PRIVATE: It's real work, labour. Lots of us spent our civilian lives doing just this kind of thing. I was a farm labourer near Bromsgrove myself. I think some of us thought that the war was going to be - not exactly a holiday, but a bit of an adventure, and in foreign parts, at that. We soon found out our mistake!

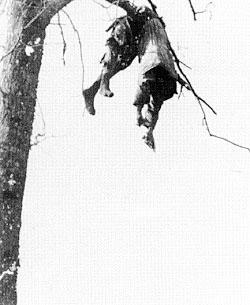

SUBALTERN: Sometime just after midnight, I'll take a reliable NCO with me into no-man's-land to see what the Boche are up to. If we come across a dead German - there're plenty of them, as you can imagine - we're supposed to take his insignia for the Intelligence johnnies at Division HQ to have a look at. Sometimes you might stumble across a forward enemy sap. If there're any signs of life you throw in a couple of Mills bombs and get back to the line as fast as possible. Or you can jump in after the grenades and try to bag a few more Germans, or capture a machine gun.

CAPTAIN: Stunts like that either get you killed - or awarded an MC. We call him Mad Mike in the Officers' Mess. The men have another expression, I believe, (turns to SERGEANT) Sergeant.

SERGEANT: (looking up and down the audience) Which I won't repeat in front of you civilians.

CORPORAL: You soon get to know the difference between a good officer and a bad one.

1ST PRIVATE: Yes. The good ones look after you. The other bloody bastards don't care for their men at all.

|

Break of day in the trenches

Isaac Rosenberg |

|

The Fallen

Wilfred Owen |

|

Afterwards

The Internet is an invaluable source of texts and images relating to the Great War and we used it extensively in the preparation of Innocents and Experience. There are far too many sites to list here, but Trenches on the Web http://www.worldwar1.com and Hellfire Corner http://www.fylde.demon.co.uk are both good places to start.

|

To trace Great War casualties, go to www.cwgc.org.

This superb site, run by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, will

enable you to discover where any British Empire or Commonwealth serviceman

or woman who died in action in the Great War or a later conflict is buried

or commemorated. They often have additional information, such as the

circumstances of death and the name and address of the parents.

The CWGC maintains the cemeteries where Commonwealth servicemen and women who died on service overseas are buried. The cemeteries are kept in immaculate order and are well worth a visit. |

All original content Copyright (C) 1998 The Arcus Theatre Company